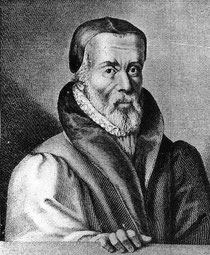

William Tyndale (sometimes spelled Tynsdale, Tindall, Tindill, Tyndall; c. 1494–1536) was an English scholar who became a leading figure in Protestant reform in the years leading up to his execution. He is well known for his translation of the Bible into English.

He was influenced by the work of Desiderius Erasmus, who made the Greek New Testament available in Europe, and by Martin Luther. While a number of partial and incomplete translations had been made from the seventh century onward, the grass-roots spread of Wycliffe's Bible resulted in a death sentence for any unlicensed possession of Scripture in English—even though all the major European languages had been translated and made available. Tyndale's translation was the first English Bible to draw directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, the first English one to take advantage of the printing press, and first of the new English Bibles of the Reformation. It was taken to be a direct challenge to the authority of both the Roman Catholic Church and English Laws to maintain church rulings. In 1530, Tyndale also wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's divorce on the grounds that it contravened Scripture.

Tyndale had to learn Hebrew in Germany due to England's active Edict of Expulsion against the Jews. He worked in an age where Greek was available to the European scholarly community for the first time in centuries. Erasmus compiled and edited Greek Scriptures into the Textus Receptus—ironically, to improve upon the Latin Vulgate—following the Renaissance-fueling Fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the dispersion of Greek-speaking intellectuals and texts into a Europe which previously had access to none. Sharing Erasmus' translation ideals, Tyndale took the ill-regarded, unpopular and awkward Middle-English "vulgar" tongue, improved upon it using Greek and Hebrew syntaxes and idioms, and formed an Early Modern English basis that Shakespeare and others would later follow and build upon as Tyndale-inspired vernacular forms took over. When a copy of his paradigm-shifting "The Obedience of a Christian Man" fell into the hands of Henry VIII, the king found the rationale to break the Church in England from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534.

In 1535, Tyndale was arrested and jailed in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) outside Brussels for over a year. In 1536 he was convicted of heresy and executed by strangulation, after which his body was burnt at the stake. His dying request that the King of England's eyes would be opened seemed to find its fulfillment just two years later with Henry's authorization of The Great Bible for the Church of England—which was largely Tyndale's own work. Hence, the Tyndale Bible, as it was known, continued to play a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across the English-speaking world and eventually, on the global British Empire. His version also worked prominently into the Geneva Bible which was taken to the New World to Jamestown in 1607, and on the Mayflower in 1620. Notably, in 1611, the 54 independent scholars who created the King James Version, drew significantly from Tyndale, as well as translations that descended from his. One estimate suggests the New Testament in the King James Version is 83% Tyndale's, and the Old Testament 76%.

Biography

Tyndale was born at some time in the period 1484–1496, possibly in one of the villages near Dursley, Gloucestershire. The Tyndale family also went by the name Hychyns (Hitchins), and it was as William Hychyns that Tyndale was enrolled at Magdalen College School, Oxford.

At Oxford

Tyndale began a Bachelor of Arts degree at Magdalen Hall of Oxford University in 1506 and received his B.A. in 1512; the same year becoming a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515 and was held to be a man of virtuous disposition, leading an unblemished life. The M.A. allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the systematic study of Scripture. As Tyndale later complained:

"They have ordained that no man shall look on the Scripture, until he be noselled in heathen learning eight or nine years and armed with false principles, with which he is clean shut out of the understanding of the Scripture."

He was a gifted linguist, over the years becoming fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, and Spanish, in addition to his native English. Between 1517 and 1521, he went to the University of Cambridge. Erasmus had been the leading teacher of Greek there from August 1511 to January 1512, but not during Tyndale's time at the university.

Tyndale became chaplain to the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury and tutor to his children in about 1521. His opinions proved controversial to fellow clergymen, and around 1522 he was called before John Bell, the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester, though no formal charges were laid.

After the harsh meeting with Bell and other church leaders, and near the end of Tyndale's time at Little Sodbury, John Foxe describes an argument with a "learned" but "blasphemous" clergyman, who had asserted to Tyndale that, "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's." Tyndale responded: "I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plow to know more of the Scriptures than thou dost!"

Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. He requested help from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist who had praised Erasmus after working together with him on a Greek New Testament. The bishop, however, declined to extend his patronage, telling Tyndale he had no room for him in his household. Tyndale preached and studied "at his book" in London for some time, relying on the help of a cloth merchant, Humphrey Monmouth. During this time he lectured widely.

In Europe

Tyndale then left England and landed on the continent, perhaps at Hamburg, in the spring of the year 1524, possibly travelling on to Wittenberg. The entry of the name "Guillelmus Daltici ex Anglia“ in the matriculation registers of the University Wittenberg has been taken to be a Latinization of "William Tyndale from England". At this time, possibly in Wittenberg, he began translating the New Testament, completing it in 1525, with assistance from Observant friar William Roy.

In 1525, publication of the work by Peter Quentell, in Cologne, was interrupted by the impact of anti-Lutheranism. It was not until 1526 that a full edition of the New Testament was produced by the printer Peter Schoeffer in Worms, a free imperial city then in the process of adopting Lutheranism. More copies were soon printed in Antwerp. The book was smuggled into England and Scotland, and was condemned in October 1526 by Bishop Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public. Marius notes that the "spectacle of the scriptures being put to the torch" "provoked controversy even amongst the faithful." Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic, his first mention in open court as a heretic being in January 1529.

Opposition to Henry VIII's divorce

In 1530, he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, opposing Henry VIII's planned divorce from Catherine of Aragon, in favour of Anne Boleyn, on the grounds that it was unscriptural and was a plot by Cardinal Wolsey to get Henry entangled in the papal courts of Pope Clement VII. The king's wrath was aimed at Tyndale: Henry asked the Emperor Charles V to have the writer apprehended and returned to England under the terms of the Treaty of Cambrai, however, the Emperor responded that formal evidence was required before extradition. Tyndale developed his case in An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue.

Betrayal and death

Eventually, Tyndale was betrayed by Henry Phillips to the imperial authorities, seized in Antwerp in 1535 and held in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) near Brussels. He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to be burned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale "was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned". Tyndale's final words, spoken "at the stake with a fervent zeal, and a loud voice", were reported as "Lord! Open the King of England's eyes."

Within four years, at the same king's behest, four English translations of the Bible were published in England, including Henry's official Great Bible. All were based on Tyndale's work.

Theological views

Tyndale denounced the practice of prayer to saints. He taught justification by faith, the return of Christ, and mortality of the soul.

Legacy

Impact on the English language

In translating the Bible, Tyndale introduced new words into the English language, and many were subsequently used in the King James Bible:

Jehovah (from a transliterated Hebrew construction in the Old Testament; composed from the Tetragrammaton YHWH)

Passover (as the name for the Jewish holiday, Pesach or Pesah

scapegoat (the goat that bears the sins and iniquities of the people in Leviticus, Chapter 16)

As well as individual words, Tyndale also coined such familiar phrases as:

lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil

knock and it shall be opened unto you

twinkling of an eye (another translation from Luther)

a moment in time

fashion not yourselves to the world

seek and you shall find

ask and it shall be given you

judge not that you not be judged

the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever

let there be light (Luther translated Genesis 1,3 as: Es werde Licht, which would beword for word translated: It will be light)

the powers that be

my brother's keeper

the salt of the earth

a law unto themselves

filthy lucre

it came to pass

gave up the ghost

the signs of the times

the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak (which is like Luther's translation of Mathew 26,41: der Geist ist willig, aber das Fleisch ist schwach; Wyclif for example translated it with: for the spirit is ready, but the flesh is sick.)

live and move and have our being

fight the good fight

Controversy over new words and phrases

The hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church did not approve of some of the words and phrases introduced by Tyndale, such as "overseer", where it would have been understood as "bishop", "elder" for "priest", and "love" rather than "charity". Tyndale, citing Erasmus, contended that the Greek New Testament did not support the traditional Roman Catholic readings. More controversially, Tyndale translated the Greek "ekklesia", (literally "called out ones") as "congregation" rather than "Church". It has been asserted this translation choice "was a direct threat to the Church's ancient—but so Tyndale here made clear, non-scriptural—claim to be the body of Christ on earth. To change these words was to strip the Church hierarchy of its pretensions to be Christ's terrestrial representative, and to award this honour to individual worshipers who made up each congregation."

Contention from Roman Catholics came not only from real or perceived errors in translation but also a fear of the erosion of their social power if Christians could read the Bible in their own language. "The Pope's dogma is bloody," Tyndale wrote in his Obedience of a Christian Man. Thomas More commented that searching for errors in the Tyndale Bible was similar to searching for water in the sea, and charged Tyndale's translation of Obedience of a Christian Man with having about a thousand falsely translated errors. Bishop Tunstall of London declared that there were upwards of 2,000 errors in Tyndale's Bible, having already in 1523 denied Tyndale the permission required under the Constitutions of Oxford (1409), which were still in force, to translate the Bible into English.

In response to allegations of inaccuracies in his translation in the New Testament, Tyndale in the Prologue to his 1525 translation wrote that he never intentionally altered or misrepresented any of the Bible in his translation, but that he had sought to "interpret the sense of the scripture and the meaning of the spirit."

While translating, Tyndale followed Erasmus' (1522) Greek edition of the New Testament. In his Preface to his 1534 New Testament ("WT unto the Reader"), he not only goes into some detail about the Greek tenses but also points out that there is often a Hebrew idiom underlying the Greek. The Tyndale Society adduces much further evidence to show that his translations were made directly from the original Hebrew and Greek sources he had at his disposal. For example, the Prolegomena in Mombert's William Tyndale's Five Books of Moses show that Tyndale's Pentateuch is a translation of the Hebrew original. His translation also drew on Latin Vulgate and Luther's 1521 September Testament.

Of the first (1526) edition of Tyndale's New Testament, only three copies survive. The only complete copy is part of the Bible Collection of Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart. The copy of the British Library is almost complete, lacking only the title page and list of contents. Another rarity of Tyndale's is the Pentateuch of which only nine remain.

Impact on the English Bible

The translators of the Revised Standard Version in the 1940s noted that Tyndale's translation inspired the great translations that followed, including the Great Bible of 1539, the Geneva Bible of 1560, the Bishops' Bible of 1568, the Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582–1609, and the King James Version of 1611, of which the RSV translators noted: "It [the KJV] kept felicitous phrases and apt expressions, from whatever source, which had stood the test of public usage. It owed most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale".

Wikipedia

Thinkers, Leaders & Exemplars

Thinkers, Leaders & Exemplars