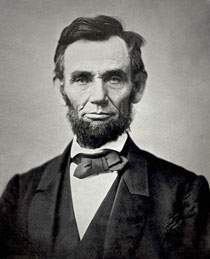

Among American heroes, Lincoln continues to have a unique appeal for his fellow countrymen and also for people of other lands.

This charm derives from his remarkable life story—the rise from humble origins, the dramatic death—and from his distinctively human and humane personality as well as from his historical role as saviour of the Union and emancipator of the slaves. His relevance endures and grows especially because of his eloquence as a spokesman for democracy. In his view, the Union was worth saving not only for its own sake but because it embodied an ideal, the ideal of self-government.

Lincoln was born in a backwoods cabin 3 miles (5 km) south of Hodgenville, Kentucky, and was taken to a farm in the neighbouring valley of Knob Creek when he was two years old.

In December 1816, faced with a lawsuit challenging the title to his Kentucky farm, Thomas Lincoln moved with his family to south-western Indiana. There, as a squatter on public land, he hastily put up a “half-faced camp”—a crude structure of logs and boughs with one side open to the weather—in which the family took shelter behind a blazing fire. Soon he built a permanent cabin, and later he bought the land on which it stood. Abraham helped to clear the fields and to take care of the crops but early acquired a dislike for hunting and fishing.

In March 1830 the Lincoln family undertook a second migration, this time to Illinois, with Lincoln himself driving the team of oxen. Having just reached the age of 21, he was about to begin life on his own.

After his arrival in Illinois, having no desire to be a farmer, Lincoln tried his hand at a variety of occupations. As a rail-splitter, he helped to clear and fence his father's new farm. As a flatboatman, he made a voyage down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, Louisiana. (This was his second visit to that city, his first having been made in 1828, while he still lived in Indiana.) Upon his return to Illinois he settled in New Salem, a village of about 25 families on the Sangamon River. There he worked from time to time as storekeeper, postmaster, and surveyor.

With the coming of theBlack Hawk War(1832), he enlisted as a volunteer and was elected captain of his company. Meanwhile, aspiring to be a legislator, he was defeated in his first try and then repeatedly re-elected to the state assembly. He considered blacksmithing as a trade but finally decided in favour of the law. Already having taught himself grammar and mathematics, he began to study law books. In 1836, having passed the bar examination, he began to practice law.

When Lincoln first entered politics,Andrew Jacksonwas president. Lincoln shared the sympathies that the Jacksonians professed for the common man, but he disagreed with the Jacksonian view that the government should be divorced from economic enterprise. “The legitimate object of government,” he was later to say, “is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done, but cannot do at all, or cannot do so well, for themselves, in their separate and individual capacities.”

While in the legislature he demonstrated that, though opposed to slavery, he was no abolitionist. In 1837, in response to the mob murder of Elijah Lovejoy, an antislavery newspaperman of Alton, the legislature introduced resolutions condemning abolitionist societies and defending slavery in the Southern states as “sacred” by virtue of the federal Constitution. Lincoln refused to vote for the resolutions. Together with a fellow member, he drew up a protest that declared, on the one hand, that slavery was “founded on both injustice and bad policy” and, on the other, that “the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils.”

During his single term in Congress (1847–49), Lincoln, as the lone Whig from Illinois, gave little attention to legislative matters. He proposed a bill for the gradual and compensated emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia, but, because it was to take effect only with the approval of the “free white citizens” of the district, it displeased abolitionists as well as slaveholders and never was seriously considered.

For about five years Lincoln took little part in politics, and then a new sectional crisis gave him a chance to re-emerge and rise to statesmanship. In 1854 his political rivalStephen A. Douglasmaneuvered through Congress a bill for reopening the entire Louisiana Purchase toslaveryand allowing the settlers of Kansas and Nebraska (with “popular sovereignty”) to decide for themselves whether to permit slaveholding in those territories. TheKansas-Nebraska Actprovoked violent opposition in Illinois and the other states of the old Northwest. It gave rise to theRepublican Partywhile speeding the Whig Party on its way to disintegration. Along with many thousands of other homeless Whigs, Lincoln soon became a Republican (1856). Before long, some prominent Republicans in the East talked of attracting Douglas to the Republican fold, and with him his Democratic following in the West. Lincoln would have none of it. He was determined that he, not Douglas, should be the Republican leader of his state and section.

In the end, Lincoln lost the election to Douglas. Although the outcome did not surprise him, it depressed him deeply. Lincoln had, nevertheless, gained national recognition and soon began to be mentioned as a presidential prospect for 1860.

With the Republicans united, the Democrats divided, and a total of four candidates in the field, he carried the election on November 6. Although he received no votes from the Deep South and no more than 40 out of 100 in the country as a whole, the popular votes were so distributed that he won a clear and decisive majority in the Electoral College.

After Lincoln's election and before his inauguration, the state of South Carolina proclaimed its withdrawal from the Union. To forestall similar action by other Southern states, various compromises were proposed in Congress. The most important, theCrittenden Compromise, included constitutional amendments guaranteeing slavery forever in the states where it already existed and dividing the territories between slavery and freedom. Although Lincoln had no objection to the first of these amendments, he was unalterably opposed to the second and indeed to any scheme infringing in the slightest upon the free-soil plank of his party's platform. “I am inflexible,” he privately wrote. He feared that a territorial division, by sanctioning the principle of slavery extension, would only encourage planter imperialists to seek new slave territory south of the American border and thus would “put us again on the highroad to a slave empire.” From his home in Springfield he advised Republicans in Congress to vote against a division of the territories, and the proposal was killed in committee. Six additional states then seceded and, with South Carolina, combined to form theConfederate States of America.

Thus, before Lincoln had even moved into the White House, a disunion crisis was upon the country. Attention, north and south, focused in particular uponFort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. This fort, still under construction, was garrisoned by U.S. troops under Major Robert Anderson. The Confederacy claimed it and, from other harbour fortifications, threatened it. Foreseeing trouble, Lincoln, while still in Springfield, confidentially requestedWinfield Scott, general in chief of the U.S. Army, to be prepared “to either hold, or retake, the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration.” In his inaugural address (March 4, 1861), besides upholding the Union's indestructibility and appealing for sectional harmony, Lincoln restated his Sumter policy as follows:

The power confided to me, will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property, and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion—no using of force against, or among the people anywhere.

Then, near the end, addressing the absent Southerners: “You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors.”

No sooner was he in office than Lincoln received word that the Sumter garrison, unless supplied or withdrawn, would shortly be starved out. Still, for about a month, Lincoln delayed acting. He was beset by contradictory advice. On the one hand, General Scott, Secretary of StateWilliam H. Seward, and others urged him to abandon the fort; and Seward, through a go-between, gave a group of Confederate commissioners to understand that the fort would in fact be abandoned. On the other hand, many Republicans insisted that any show of weakness would bring disaster to their party and to the Union. Finally Lincoln ordered the preparation of two relief expeditions, one for Fort Sumter and the other for Fort Pickens, in Florida. (He afterward said he would have been willing to withdraw from Sumter if he could have been sure of holding Pickens.) Before the Sumter expedition, he sent a messenger to tell the South Carolina governor:

I am directed by the President of the United States to notify you to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort-Sumpter [sic] with provisions only; and that, if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition, will be made, without further notice, or in case of an attack upon the Fort.

Without waiting for the arrival of Lincoln's expedition, the Confederate authorities presented to Major Anderson a demand for Sumter's prompt evacuation, which he refused. On April 12, 1861, at dawn, the Confederate batteries in the harbour opened fire.

“Then, and thereby,” Lincoln informed Congress when it met on July 4, “the assailants of the Government, began the conflict of arms.”

Lincoln's primary aim was neither to provoke war nor to maintain peace. In preserving the Union, he would have been glad to preserve the peace also, but he was ready to risk a war that he thought would be short.

The war lasted 4 years and was eventually won by Lincoln. In order to maintain the Union, which was his prime objective, he had to forego many opportunities to abolish slavery

There can be no doubt of Lincoln's deep and sincere devotion to the cause of personal freedom. Before his election to the presidency he had spoken often and eloquently on the subject. In 1854, for example, he said he hated the Douglas attitude of indifference toward the possible spread of slavery to new areas. “I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself,” he declared. “I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world; enables the enemies of free institutions with plausibility to taunt us as hypocrites….” In 1855, writing to his friend Joshua Speed, he recalled a steamboat trip the two had taken on the Ohio River 14 years earlier. “You may remember, as I well do,” he said, “that from Louisville [Kentucky] to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border.”

"My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

Meanwhile, in response to the rising antislavery sentiment, Lincoln came forth with an emancipation plan of his own. According to his proposal, the slaves were to be freed by state action, the slaveholders were to be compensated, the federal government was to share the financial burden, the emancipation process was to be gradual, and the freedmen were to be colonized abroad. Congress indicated its willingness to vote the necessary funds for the Lincoln plan, but none of the border slave states were willing to launch it, and in any case few African American leaders desired to see their people sent abroad.

While still hoping for the eventual success of his gradual plan, Lincoln took quite a different step by issuing his preliminary (September 22, 1862) and his final (January 1, 1863. This famous decree, which he justified as an exercise of the president's war powers, applied only to those parts of the country actually under Confederate control, not to the loyal slave states nor to the federally occupied areas of the Confederacy. Directly or indirectly the proclamation brought freedom during the war to fewer than 200,000 slaves. Yet it had great significance as a symbol. It indicated that the Lincoln government had added freedom to reunion as a war aim, and it attracted liberal opinion in England and Europe to increased support of the Union cause.

Lincoln himself doubted the constitutionality of his step, except as a temporary war measure. After the war, theslavesfreed by the proclamation would have risked re-enslavement had nothing else been done to confirm their liberty. But something else was done: the Thirteenth Amendment was added to theConstitution, and Lincoln played a large part in bringing about this change in the fundamental law. Through the chairman of the Republican National Committee he urged the party to include a plank for such an amendment in its platform of 1864. The plank, as adopted, stated that slavery was the cause of the rebellion, that the president's proclamation had aimed “a death blow at this gigantic evil,” and that a constitutional amendment was necessary to “terminate and forever prohibit” it. When Lincoln was reelected on this platform and the Republican majority in Congress was increased, he was justified in feeling, as he apparently did, that he had a mandate from the people for the Thirteenth Amendment. The newly chosen Congress, with its overwhelming Republican majority, was not to meet until after the lame duck session of the old Congress during the winter of 1864–65. Lincoln did not wait. Using his resources of patronage and persuasion upon certain of the Democrats, he managed to get the necessary two-thirds vote before the session's end. He rejoiced as the amendment went out to the states for ratification, and he rejoiced again and again as his own Illinois led off and other states followed one by one in acting favourably upon it. (He did not live to rejoice in its ultimate adoption.)

Lincoln deserves his reputation as the Great Emancipator. His claim to that honour, if it rests uncertainly upon his famous proclamation, has a sound basis in the support he gave to the antislavery amendment. It is well founded also in his greatness as the war leader who carried the nation safely through the four-year struggle that brought freedom in its train. And, finally, it is strengthened by the practical demonstrations he gave of respect for human worth and dignity, regardless of colour. During the last two years of his life he welcomed African Americans as visitors and friends in a way no president had done before. One of his friends was the distinguished former slaveFrederick Douglass, who once wrote: “In all my interviews with Mr. Lincoln I was impressed with his entire freedom from prejudice against the coloured race.”

Extracts from:

Richard N. Current

Encyclopædia Britannica

Thinkers, Leaders & Exemplars

Thinkers, Leaders & Exemplars